Tamsin Blanchard, Fashion Revolutionary & Journalist

It’s such a simple question: “Who Made My Clothes?” But a straightforward answer, even if a brand is willing to name the factory where they make their clothes, can unleash a whole chain of complex issues. From conditions in factories, rates of pay, and working hours, to even murkier ones when you start to look beyond the textile mills to the cotton farms where further exploitation can happen. Not least, possibilities of forced labour as we’ve seen recently with Uighar and other Turkic Muslim minority people forced to work in the cotton fields of the Xinjiang region of China which produces 20% of the world’s cotton.

For Fashion Revolution, the campaign I have been involved with since it began after the Rana Plaza factory disaster in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013 when over 1,100 garment workers were crushed to death after the factory they were working in collapsed – despite warnings it was unsafe – the question was designed to start a revolution within the clothing industry.

Eight years after the first Fashion Revolution Week, set up to remember Rana Plaza and ensure such a disaster could never be allowed to happen again, that question has been asked millions of times. It has pricked the conscience of fashion lovers as well as those employed by the industry around the globe.

Nobody wants to feel they are implicit in the exploitation of others every time they buy a T-shirt or a new dress. The campaign now has teams run by passionate and dedicated volunteers all around the world, from Argentina to Zimbabwe, each with their own challenges and priorities.

Transparency – ensuring a brand or retailer knows who is in their supply chain, how those people are being treated, whether there is harassment and bullying on the shop floor, if the workplace is safe, or if they are allowed to be part of a workers’ union, and understanding where the raw materials come from and how they are farmed, or processed, and what chemicals are involved – is at the root of everything Fashion Revolution does. As co-founder Carry Somers says: “If we can’t see it, we can’t fix it.”

-(1).jpg%3Fv%3D0&c_options=)

Image Credit: Tamsin Blanchard

When Rana Plaza happened, I was working as the Fashion Features Director of the Telegraph Magazine. I had written Green is the New Black in 2007, a quirky guide on how to save the world in style. But until 2013, the enormous social and environmental impacts of the fashion industry were marginal issue, given little airtime within the mainstream fashion coverage. Rana Plaza was the first time the working conditions of women – 80% of garment workers are female – in the fashion industry was given real air time. The factory collapse was front page news. It was impossible to ignore. And while I was working with a lot of luxury brands who quickly sought to distance themselves and lay the blame at the feet of the fast fashion, mass production brands, it soon became clear that nobody in the fashion industry was innocent.

There is only one way that clothes can be produced as cheaply and in such huge volumes as they now are: cheap labour, long hours, the exploitation of the poorest in our society so that multinational brands can get bigger and richer.

There are other factors at play too. The pandemic has highlighted the whole rotten system. Over the past year, as shops have closed their doors unable to sell the stock on the rails, and people around the world locked down, we have seen brands refusing to pay factories for orders they had already placed, and which the factories had produced.

It turns out the brands have their cake and eat it all the way, forcing factories, desperate for their orders, to front the costs of production. The workers ultimately bore the brunt. There’s a template to send to brands if you are concerned that they have cancelled orders. https://www.fashionrevolution.org/covid19/

My initial motivation in asking Who Made My Clothes? was about social injustice, which over the years has been spurred on by the Me Too movement as well as Black Lives Matter laying bare the entire industry’s foundations built on colonialism. But, the climate emergency has become increasingly urgent too.

Last year, Fashion Revolution introduced the hashtag #WhatsInMyClothes highlighting the chemicals and the synthetics in the clothes we wear, (yes, polyester = plastic) and particularly the huge issues around microplastics.

There are many ways to get involved. My role at the campaign is to curate a programme of designer Fashion Open Studios to highlight the positive changes happening in industry. Follow us @fashionopenstudio for two new events planned for London Fashion Week. I also work on other projects including the charity’s zines designed to educate and engage but also to raise much needed funds to sustain Fashion Revolution’s ongoing work to push for tangible policy change as well as all-important cultural change.

In 2018, I edited a zine called Fashion Environment Change. It’s a bite size booklet written by experts in the field, a very simple A-Z highlighting everything from a one paragraph introduction to the Anthropocene to the impact of viscose production on the biodiversity of our forests. It distills a lot of big issues into short snippets of information, designed to point you in the right direction and find out more if you want to. There are still some copies available to buy, alongside the other zines in the series that look at craft and particularly issues around cultural appropriation, and most recently a deeper dive into how the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals impact areas of the industry.

You will also find the 2021 Year Planner – How to Be a Fashion Revolutionary 365 Days a Yearwhich is your indispensable £2 guide to special days and events, so you can plan your own activism and help you prepare for Fashion Revolution Week if you want to plan some activities with friends and your local community.

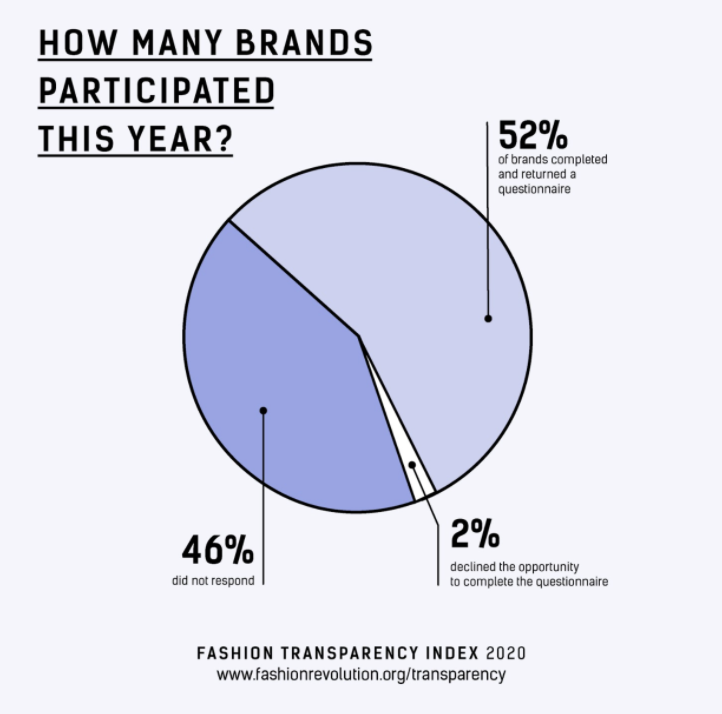

There are so many other free downloadable resources on the Fashion Revolution website, I really recommend having a poke about, particularly the annual Fashion Transparency Index which rates 250 of the biggest brands on how much information they are disclosing on their social and environmental policies.

Perhaps the easiest way to keep up to date with the issues and how you can get involved is the non-stop conversation happening on the Instagram channel @fash_rev with an addictive mix of educational posts, facts, and explanations. My favourite is the definitions series in collaboration with @entrylevelactivist which is brilliant in breaking down some of the jargon that often tangles up some of the information around fashion and sustainability.

One thing I have learnt over the years is that the situation evolves constantly, new information emerges, new research debunks the old. The one question that always remains – and is unfortunately still as relevant as ever – is Who Made My Clothes? If you haven’t already, and if you are curious, I urge you to get involved.

We need to show the brands and retailers that this stuff is really important to us and they need to take responsibility for what they make and how they make it. The appalling inequality and exploitation of the people and our planet needs to stop.

You don’t need to wait until Fashion Revolution Week. Just tag your favourite brand and ask them #whomademyclothes? Some progress has been made and hopefully you will be pleasantly surprised. If not, you may well trigger a small ripple that turns into a tidal wave.

If you enjoyed reading this, click here to check out How to be more activist in 2021. 7 UK petitions to sign from your sofa.